The exotic and easily recognized ostrich egg is found surprisingly often by archaeologists working all around the Mediterranean. Evidence for its use is found as early as the 7th millennium B.C. While it yields large amounts of protein and is thus best known as a dietary supplement, it has many other uses, and is therefore of substantial interest to scholars who study ancient art, crafts, trade, and religion (Caubet 1983, Finet 1982, Laufer 1926, Reese 1985). A survey of these may help us to understand why the ancient Libyans offered whole ostrich eggs to the Egyptian, Pharaoh as items of tribute, and why broken shells ended up in occupation debris on Bates’ Island.

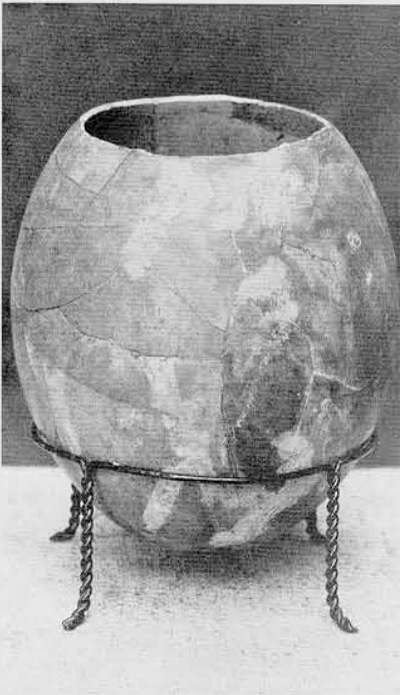

From Laufer 1926: Pl. 1. Reproduced by permission of the Field Museum of Natural History [Neg. no. 50970], Chicago)

Besides serving as a container, the emptied ostrich egg has other practical uses. For example, various ancient peoples shaped the shell into arrow heads and potters’ combs. Babylonian and Assyrian texts record its medicinal as well as its magical values (Finet 1982:75), and ground ostrich eggshell is still said to be able to protect one from blindness.

The use of ostrich eggs for religious purposes is well documented. Eggs were offered in ancient Greek sanctuaries, where they served as a symbol of fertility and prosperity, and are still displayed in churches. Empty ostrich eggshells, often decorated with painted or incised designs, were placed in graves as early as the 5th millennium B.C. This practice is relatively common, and is documented for cultures dated from the 4th to the 2nd millennia B.C. including Predynastic and Pharaonic Egypt; Early Dynastic Nubia; and Bronze Age Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Syro-Palestine, and Mesopotamia (Fig.11). In the later 1st millennium B.C., ostrich eggs were used as grave goods by the Punic Phoenicians and Etruscans, symbolizing resurrection and eternal life, as well as providing “food” for the deceased. Today, ostrich eggs are still used by Moslems to honor the dead, being hung near or above the place of burial.

Ornamental uses of the ostrich egg are also numerous. In modern times they hang from the ceilings of North African dwellings, and have been observed adorning the roofs of straw huts in the Sudan. The eggs may even be gilded and placed in chandeliers, as known from a monastery in the Sinai. The relatively thick, smooth shells make an excellent raw material for small ornaments. Disc beads and other shapes cut from the egg’s relatively thick shell have been used in pendants, necklaces, belts, and anklets since Neolithic times, and are still made by the (Kung San people of the Kalahari desert in southern Africa (Fig. 8).

This short article comes from the full article, On Ostrich Eggs and Libyans–Traces of a Bronze Age People from Bates’ Island, Egypt

http://penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/29-3/On1.pdf

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario