Chapter IV. The Reliefs

In reliefs the representation of Nature is

complicated by the inevitable use of some conventions, and some kind of

perspective, to reduce solid objects to a plane delineation. It follows that for

the study of naturalistic art they are inferior to statuary, though they give rise to a whole

system of artistic conventions which are of interest in themselves. It appears

that among most races drawings precede reliefs, and hence relief must

be looked on as developed drawing, and not as trammelled statuary. The oldest

reliefs are those of the prehistoric ivory carvings (see fig. 3), in which we see

maintained the pictorial convention of crossing lines to substantiate the

outline of a solid body, although the body was now expressed by the relief. A

large quantity of ivory reliefs showing rows of animals were found at

Hierakonpolis, belonging to the earliest historic times. Of the same class are

the reliefs upon the primitive figures from Koptos (fig. 51). These comprise the

elephant, stag's head, and swordfish, as well as the hyaena and ox. The design

is spirited, and seizes the characteristics of the animals; while hills are

conventionally shown by lumps under each foot. The method of work is by bruising

out the surface with a pointed stone pick around the outline, and so lowering

the surrounding ground (here shaded), while the body of the animal remains of

the original face of the stone.

51. Hyaena and bull 53. Group of

animals.

51. Hyaena and bull 53. Group of

animals.

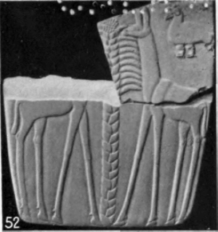

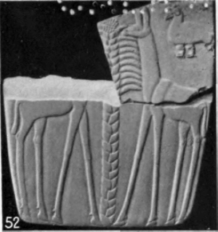

52. Gazelles and palm 54. King Narmer.

52. Gazelles and palm 54. King Narmer.

The next stage is that of the astonishing slate reliefs. The purely artistic motive is seen in the group of two long-necked gazelles with a palm-tree (fig. 52). The detail of the forms of the joints and the general pose of the animals is excellent, and the feeling for the graceful, slender outline and smooth surfaces is enforced by the rugged palm stem placed between the gazelles. The love of the strange and wild elements is seen in the rout of animals, real and mythical, in fig. 53, which shows the lion, giraffe, wild ox, and many kinds of deer, well known to the early artists.

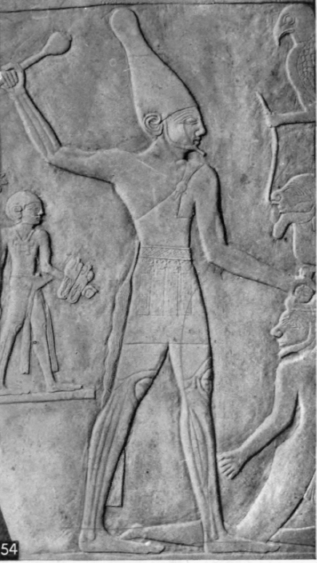

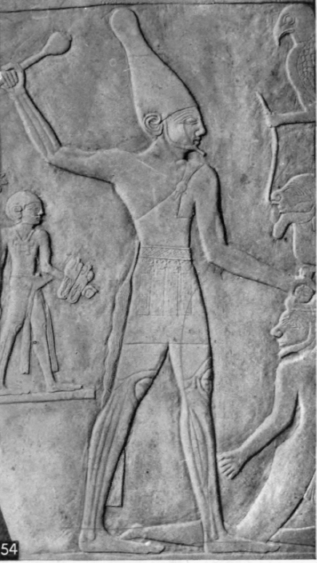

The figure of King Narmer (fig. 54) is the historical point in these slate carvings. As it is more advanced in style than any of the others, it shows that they all belong to the age just before the 1st dynasty, about 5500 B.C. Here the pose and jointing are excellent, and the muscles are proclaimed by the artist as the results of his observation. The later Egyptian canon is observed that a straight line should pass through the middle of the head, middle of the trunk, point of the backward knee, and middle between the heels: only, as the king is here leaning forward in action, the line is not vertical as it is in later standing figures. The facial characters of the king and his foe are well distinguished; altogether five different types of race are shown on these early carvings. The surface of the slate has been worked down with a metal scraper, shown by the parallel grooves in the face.

On reaching the beginning of the pyramid age the finest work is seen in the three wooden panels of Ra-hesy (fig. 55, frontispiece). The anatomy is full, though not so excessive as in the earlier work. The facial curves are carefully rendered, and the mouth is excellently formed. The eye is of course placed in front view, as it always was by Egyptians. The whole figure has an air of stark vigour, which is fitting to a high official who managed a dozen different offices.

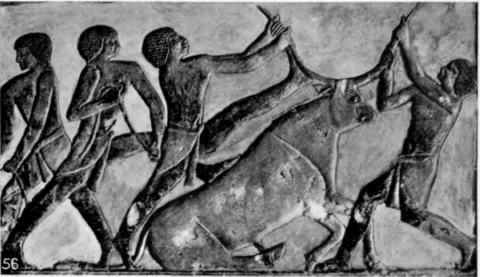

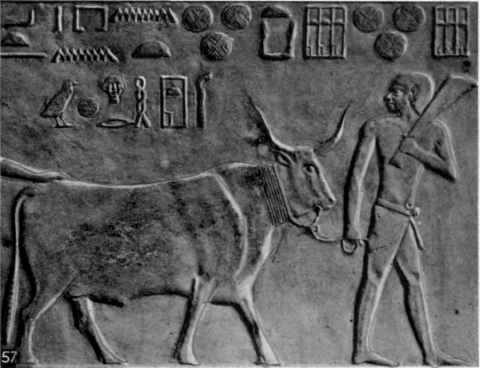

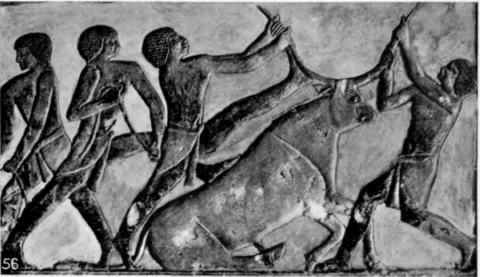

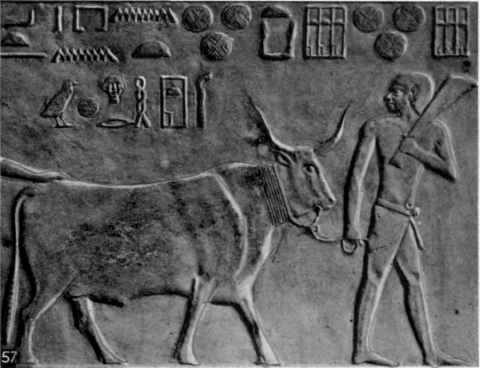

The multitude of the mastaba tomb-chapels of the pyramid age contain so many thousands of scenes, illustrating every act of life of men and animals, that it is impossible to give any view of their variety. Here we can only give two scenes illustrating composition. In fig. 56 is a group of men dragging down an ox for sacrifice. The arrangement of the lines is clear, each figure stands out separately, the action is vigorous and simple. Another scene of an ox-herd (fig. 57) shows quiet motion, with the unusual turning of the head. This might be thought unnatural, but exactly the same twist of the body may be seen among Egyptians now. This style of relief deteriorated in the VIth dynasty, and then continuously decayed until the middle of the Xlth dynasty, by which time it has reached a most degraded state.

Suddenly, in the middle of the Xlth dynasty, a new style of careful elaboration begins to appear, a true archaic germ of a new school. This rapidly grew, until at the later part of that dynasty there is a stiff and over-elaborate style, which is well shown in the figure of the princess Kauat having her hair curled (fig. 58). The eyes of all the figures are gibbous, with a moderate fossa; the lips have usually a sharp edge, though sometimes merely rounded; and there is the beginning of facial modelling. the pyramid age contain so many thousands of scenes, illustrating every act of life of men and animals, that it is impossible to give any view of their variety. Here we can only give two scenes illustrating composition. In fig. 56 is a group of men dragging down an ox for sacrifice. The arrangement of the lines is clear, each figure stands out separately, the action is vigorous and simple. Another scene of an ox-herd (fig. 57) shows quiet motion, with the unusual turning of the head. This might be thought unnatural, but exactly the same twist of the body may be seen among Egyptians now. This style of relief deteriorated in the VIth dynasty, and then continuously decayed until the middle of the Xlth dynasty, by which time it has reached a most degraded state.

Suddenly, in the middle of the Xlth dynasty, a new style of careful elaboration begins to appear, a true archaic germ of a new school. This rapidly grew, until at the later part of that dynasty there is a stiff and over-elaborate style, which is well shown in the figure of the princess Kauat having her hair curled (fig. 58). The eyes of all the figures are gibbous, with a moderate fossa; the lips have usually a sharp edge, though sometimes merely rounded; and there is the beginning of facial modelling.

56. The sacrifice.

56. The sacrifice.

57. The ox-herd.

In the XIIth dynasty the surface modelling became elaborate, most delicate gradations being wrought with faint outlines, as seen in the Mem-phite head, fig. 6. A bold high relief and simpler treatment was followed by the Theban school, as in fig. 59 of the god Ptah and Senusert I embracing. The use of sunk relief, as fig. 58, was as early as the IVth dynasty, though most of the tomb sculptures are in high relief. Sunk relief became commoner in the MiddleKingdom, and almost universal in the New Kingdom. It saved a large amount of labour, and it protected the sculptures from injury; but it is so forcible a convention that it is never so pleasing as the raised work.

The XVIIIth dynasty opens with another revival of art, but yet it never reached the levels of the earlier ages. The profusion of reliefs of Thebes and other great sites has made the style of the XVIIIth and XIXth dynasties the most familiar to us, but its inferiority to that of the previous periods is more obvious the more it is studied. The sculptures of Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri are celebrated, yet the detail in fig. 60 is not rich. There is scarcely any modelling of face or muscles, mere flat surfaces sufficing; there is but little expression in the features; and the whole effect is flat and tame. More character appears under Amenhotep III (fig. 61), though even here there is none of the muscular detail which was constantly shown in early work. The features smile gracefully without any real expression, and the trivial details of dress are worked out to give a picturesque elaboration. The taste for mere prettiness and graceful personalities ruled more and more as the XVIIIth dynasty developed.

58. Toilet of princess.

58. Toilet of princess.

59. Senusert I and Ptah.

60. Hatshepsut 61. Servant of

Kha-em-hat.

60. Hatshepsut 61. Servant of

Kha-em-hat.

62. Akhenaten and queen.

At last this taste, stimulated by the influence of the Greek art and its love of expressing motion, broke all bounds in the movement under Akhenaten. The example in fig. 62 gives the essence of Atenism. The natural but ungainly attitudes, the flourishing ribands, the heavy collars and kilt, the ungraceful realism of the figures, the loss of all expression and detail of structure, - all these show the death of a permanentartinthe fever of novelty and vociferation.

This ferment being passed, the Egyptian went back on his older style; but it had lost its life, it could only be copied. The exquisite smoothness and finish of the good work of Sety I at Abydos is entirely lifeless and destitute of observation. It has no anatomical detail, but was made by well-constructed human machines who could not express an emotion which they did not feel.

The historical scenes of the great sculptures of Karnak are full of interest, but almost destitute of art. Some parts of the work of Ramessu III at Medinet Habu show more observation, such as the hunting scene, fig. 63. The wild bulls are well studied, and the marsh-plants with feathery tops show a real appreciation of natural growth and beauty.

Under the XXVIth dynasty came the deliberate imitation of the work of the Old Kingdom. In a few cases this is passably done, and even some invention may be seen. But in general there is only a lifeless imitation of various parts clumsily put together. One of the best pieces of such art is the procession of youths and maids carrying animals and farm produce (fig. 64). The forms are true, there is none of the later exaggeration (as in fig. 10), and there is a loving touch in the details, especially of the animals, which belongs to the true artist. Observe how the girls carry the flowers and the birds, while the boys take the heavy loads of papyrus stems and a calf and a basket of flour. Such work is the last flicker of Egyptian art in reliefs, and nothing later claims our notice.

63. Bulls in marshes.

63. Bulls in marshes.

64. Bearers of offerings.

Earliest Reliefs

51. Hyaena and bull 53. Group of

animals.

51. Hyaena and bull 53. Group of

animals.

52. Gazelles and palm 54. King Narmer.

52. Gazelles and palm 54. King Narmer.The next stage is that of the astonishing slate reliefs. The purely artistic motive is seen in the group of two long-necked gazelles with a palm-tree (fig. 52). The detail of the forms of the joints and the general pose of the animals is excellent, and the feeling for the graceful, slender outline and smooth surfaces is enforced by the rugged palm stem placed between the gazelles. The love of the strange and wild elements is seen in the rout of animals, real and mythical, in fig. 53, which shows the lion, giraffe, wild ox, and many kinds of deer, well known to the early artists.

The figure of King Narmer (fig. 54) is the historical point in these slate carvings. As it is more advanced in style than any of the others, it shows that they all belong to the age just before the 1st dynasty, about 5500 B.C. Here the pose and jointing are excellent, and the muscles are proclaimed by the artist as the results of his observation. The later Egyptian canon is observed that a straight line should pass through the middle of the head, middle of the trunk, point of the backward knee, and middle between the heels: only, as the king is here leaning forward in action, the line is not vertical as it is in later standing figures. The facial characters of the king and his foe are well distinguished; altogether five different types of race are shown on these early carvings. The surface of the slate has been worked down with a metal scraper, shown by the parallel grooves in the face.

On reaching the beginning of the pyramid age the finest work is seen in the three wooden panels of Ra-hesy (fig. 55, frontispiece). The anatomy is full, though not so excessive as in the earlier work. The facial curves are carefully rendered, and the mouth is excellently formed. The eye is of course placed in front view, as it always was by Egyptians. The whole figure has an air of stark vigour, which is fitting to a high official who managed a dozen different offices.

The multitude of the mastaba tomb-chapels of the pyramid age contain so many thousands of scenes, illustrating every act of life of men and animals, that it is impossible to give any view of their variety. Here we can only give two scenes illustrating composition. In fig. 56 is a group of men dragging down an ox for sacrifice. The arrangement of the lines is clear, each figure stands out separately, the action is vigorous and simple. Another scene of an ox-herd (fig. 57) shows quiet motion, with the unusual turning of the head. This might be thought unnatural, but exactly the same twist of the body may be seen among Egyptians now. This style of relief deteriorated in the VIth dynasty, and then continuously decayed until the middle of the Xlth dynasty, by which time it has reached a most degraded state.

Suddenly, in the middle of the Xlth dynasty, a new style of careful elaboration begins to appear, a true archaic germ of a new school. This rapidly grew, until at the later part of that dynasty there is a stiff and over-elaborate style, which is well shown in the figure of the princess Kauat having her hair curled (fig. 58). The eyes of all the figures are gibbous, with a moderate fossa; the lips have usually a sharp edge, though sometimes merely rounded; and there is the beginning of facial modelling. the pyramid age contain so many thousands of scenes, illustrating every act of life of men and animals, that it is impossible to give any view of their variety. Here we can only give two scenes illustrating composition. In fig. 56 is a group of men dragging down an ox for sacrifice. The arrangement of the lines is clear, each figure stands out separately, the action is vigorous and simple. Another scene of an ox-herd (fig. 57) shows quiet motion, with the unusual turning of the head. This might be thought unnatural, but exactly the same twist of the body may be seen among Egyptians now. This style of relief deteriorated in the VIth dynasty, and then continuously decayed until the middle of the Xlth dynasty, by which time it has reached a most degraded state.

Suddenly, in the middle of the Xlth dynasty, a new style of careful elaboration begins to appear, a true archaic germ of a new school. This rapidly grew, until at the later part of that dynasty there is a stiff and over-elaborate style, which is well shown in the figure of the princess Kauat having her hair curled (fig. 58). The eyes of all the figures are gibbous, with a moderate fossa; the lips have usually a sharp edge, though sometimes merely rounded; and there is the beginning of facial modelling.

Old Kingdom Reliefs

56. The sacrifice.

56. The sacrifice.57. The ox-herd.

In the XIIth dynasty the surface modelling became elaborate, most delicate gradations being wrought with faint outlines, as seen in the Mem-phite head, fig. 6. A bold high relief and simpler treatment was followed by the Theban school, as in fig. 59 of the god Ptah and Senusert I embracing. The use of sunk relief, as fig. 58, was as early as the IVth dynasty, though most of the tomb sculptures are in high relief. Sunk relief became commoner in the MiddleKingdom, and almost universal in the New Kingdom. It saved a large amount of labour, and it protected the sculptures from injury; but it is so forcible a convention that it is never so pleasing as the raised work.

The XVIIIth dynasty opens with another revival of art, but yet it never reached the levels of the earlier ages. The profusion of reliefs of Thebes and other great sites has made the style of the XVIIIth and XIXth dynasties the most familiar to us, but its inferiority to that of the previous periods is more obvious the more it is studied. The sculptures of Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri are celebrated, yet the detail in fig. 60 is not rich. There is scarcely any modelling of face or muscles, mere flat surfaces sufficing; there is but little expression in the features; and the whole effect is flat and tame. More character appears under Amenhotep III (fig. 61), though even here there is none of the muscular detail which was constantly shown in early work. The features smile gracefully without any real expression, and the trivial details of dress are worked out to give a picturesque elaboration. The taste for mere prettiness and graceful personalities ruled more and more as the XVIIIth dynasty developed.

Middle Kingdom Reliefs

58. Toilet of princess.

58. Toilet of princess.59. Senusert I and Ptah.

60. Hatshepsut 61. Servant of

Kha-em-hat.

60. Hatshepsut 61. Servant of

Kha-em-hat.62. Akhenaten and queen.

At last this taste, stimulated by the influence of the Greek art and its love of expressing motion, broke all bounds in the movement under Akhenaten. The example in fig. 62 gives the essence of Atenism. The natural but ungainly attitudes, the flourishing ribands, the heavy collars and kilt, the ungraceful realism of the figures, the loss of all expression and detail of structure, - all these show the death of a permanentartinthe fever of novelty and vociferation.

This ferment being passed, the Egyptian went back on his older style; but it had lost its life, it could only be copied. The exquisite smoothness and finish of the good work of Sety I at Abydos is entirely lifeless and destitute of observation. It has no anatomical detail, but was made by well-constructed human machines who could not express an emotion which they did not feel.

The historical scenes of the great sculptures of Karnak are full of interest, but almost destitute of art. Some parts of the work of Ramessu III at Medinet Habu show more observation, such as the hunting scene, fig. 63. The wild bulls are well studied, and the marsh-plants with feathery tops show a real appreciation of natural growth and beauty.

Under the XXVIth dynasty came the deliberate imitation of the work of the Old Kingdom. In a few cases this is passably done, and even some invention may be seen. But in general there is only a lifeless imitation of various parts clumsily put together. One of the best pieces of such art is the procession of youths and maids carrying animals and farm produce (fig. 64). The forms are true, there is none of the later exaggeration (as in fig. 10), and there is a loving touch in the details, especially of the animals, which belongs to the true artist. Observe how the girls carry the flowers and the birds, while the boys take the heavy loads of papyrus stems and a calf and a basket of flour. Such work is the last flicker of Egyptian art in reliefs, and nothing later claims our notice.

Late Reliefs

63. Bulls in marshes.

63. Bulls in marshes.64. Bearers of offerings.

Read more: http://chestofbooks.com/arts/ancient/Ancient-Egypt-Arts-And-Crafts/Chapter-IV-The-Reliefs.html#ixzz20c8wRXMf

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario