The Statuary. Part 4

We now turn to the minor work in wood. In

the Old Kingdom, wood was frequently carved on a large scale; of the Middle

Kingdom there is the statue of King Hor; but under the New Kingdom the only

large figures are some rather coarse funeral statues. On the other hand, in

small figures there is a profusion of wood-carving. The wooden us-habtis are

often beautifully treated; the draped figures of women are graceful and

dignified, with minute working of the hair and dress; the grotesque figures of

toilet objects are full of character; but here our space limits us to one class,

and we give the nude figures (figs. 40-42), as such are rarely found in other

material.

The little negress (fig. 40), carved in ebony, is part of a group representing her carrying a tray, which is supported by a monkey before her. But these accessories are inferior, and merely hide the figure; the edge of the tray has been slightly cut in on the breast and thus disfigured it. The detail of this statuette is better than any other such work; the perfect pose of the attitude, the poise of the head, the fulness of the muscles, the innocent gravity of the expression, are all excellent.

Other figures are carved in the handles of toilet trays. The girl in fig. 41 holding flowers and birds is on a smaller and coarser scale than the preceding, but is excellent in expression and in the modelling of the trunk. The damsel playing a lute on her boat amid the papyrus thicket (fig. 42) shows one of the graceful adjuncts of water-parties in high life. The length of leg is exaggerated to harmonise with the long stems around; but the pose is skilfully seized, the distance of the feet being needful for balance in a little shallop, while the cling of the thighs is maintained. There is more self-consciousness and deliberate effect in this expression than in that of the little girls seen before.

The age of decadence now begins with the Ra-messides. One fine piece arrests us in the black granite statue of Ramessu II (fig. 43), of which an entire view is given in fig. 11. The whole pose is fairly good, the face looking down toward the spectator below. The king is no longer the dignified organiser of the Old Kingdom, with a vision far away beyond everyday matters, but he is obviously considering the opinion of the man in front of him. The detail is almost equal to that of the previous dynasty; the eye is natural, the nose rather formal, the lips with the sharp edge even more developed than before, and the chin and throat less modelled. The elbow is carefully wrought, bringing out the fold of flesh and the muscle separately, the accuracy of which is questionable.

A good example of a private sculpture is the head of Bak-en-khonsu (fig. 44). The eye is only slightly indicated, leaning to the conventional blocking out seen in figs. 91 and 137. The profile is good, and the lips are less exaggerated than in the royal statues. The artist could give all his attention to the face alone, as the figure is entirely hidden in an almost cubic block, which represents the man seated with knees drawn up before the chest.

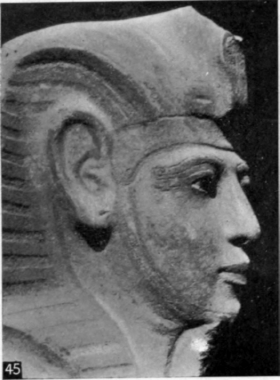

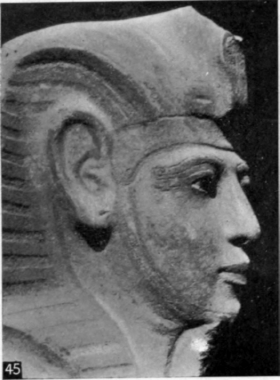

The head of Merenptah (fig. 45) shows him as inheriting and imitating his father's face and attitude. The style is cold and formal; the eyes are so forward as to be even beyond the plane of the forehead, and scarcely capped by the brow. But the nose and lips are natural and free of the forcing which is seen rather earlier. There is no attempt at any delicacy of facial curves, and the chin and throat are masked by the official beard. As this is in gray granite, and was executed as the ka statue of the king's personal temple, it may be taken as the best that could be done at that time.

43. Ramessu II 45. Merenptah.

43. Ramessu II 45. Merenptah.

44. Bak-en-khonsu 46. Taharqa.

44. Bak-en-khonsu 46. Taharqa.

A different feeling comes in with the massive individual portrait of Taharqa (fig. 46). The facial muscles are strongly marked, but the mouth is singularly unformed, and is exactly the opposite of that in the strong type of fig. 34. The eyes are of the gibbous form, with a long slot of lachrymal fossa, which is also shown in the kindred figure of Queen Amenardys (fig. 47). The style is not akin to any other Egyptian work, and it seems as if an entirely different physiognomy had challenged the sculptor and made him drop his usual treatment and study Nature afresh.

The alabaster statue of Amenardys (fig. 47) is disproportioned as a whole, though parts are good separately. It has just the faults due to an imitator who does not trust to observation. The head is too large, the jointing is weak. Each of the features is fairly well rendered; and within the limits of later mannerism there is no forcing or exaggeration.

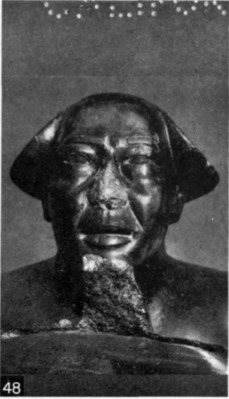

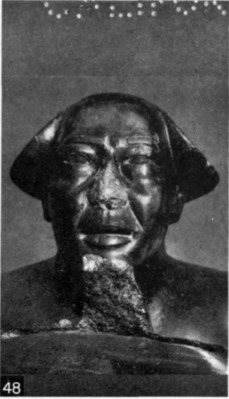

The portrait of Mentu-em-hat (fig. 48) belongs to the same style as that of Taharqa, and both are in black granite. The eyes seem too small, but this is rather due to the depth and massiveness of the jaws, which overweight the face. The apparent disproportion in the low forehead is only due to the photograph being taken too close and low down. The height above the eyes is really equal to that down to the upper edge of the chin. The facial curves are carefully observed, and we can well credit this with being a true portrait of the capable governor of Thebes who continued in office under Taharqa and Tanut-amen, and who repaired the devastations of the Assyrian invasion.

A head broken from a statue, found at Memphis (fig. 49), is remarkable for the deep and searching modelling. The bony structure, the facial muscles, and the surface folds are all scrupulously observed. The artist's triumph is shown in the harmony and the living character which he has infused into his laborious precision. Very rarely can a man rise superior to such a rigorous training. The character of work is scarcely Egyptian; it belongs rather to the same school as the republican Roman portraits, but is earlier than those, as it has more precision of detail.

47. Amenardys 49. Basalt head.

47. Amenardys 49. Basalt head.

48. Mentu-em-hat 50. Wooden head.

48. Mentu-em-hat 50. Wooden head.

Lastly, we have one of the best examples of Greek influence in Egypt shown by the wood-carving of a coffin (fig. 50). The long narrow face shaded by thick wavy hair is Greek in feeling, while the feather head-dress is old Egyptian. Unfortunately, the decay of the wood has broken the surface, but it still remains an impressive example of Egyptian influence on art which is mainly Greek.

The little negress (fig. 40), carved in ebony, is part of a group representing her carrying a tray, which is supported by a monkey before her. But these accessories are inferior, and merely hide the figure; the edge of the tray has been slightly cut in on the breast and thus disfigured it. The detail of this statuette is better than any other such work; the perfect pose of the attitude, the poise of the head, the fulness of the muscles, the innocent gravity of the expression, are all excellent.

Other figures are carved in the handles of toilet trays. The girl in fig. 41 holding flowers and birds is on a smaller and coarser scale than the preceding, but is excellent in expression and in the modelling of the trunk. The damsel playing a lute on her boat amid the papyrus thicket (fig. 42) shows one of the graceful adjuncts of water-parties in high life. The length of leg is exaggerated to harmonise with the long stems around; but the pose is skilfully seized, the distance of the feet being needful for balance in a little shallop, while the cling of the thighs is maintained. There is more self-consciousness and deliberate effect in this expression than in that of the little girls seen before.

The age of decadence now begins with the Ra-messides. One fine piece arrests us in the black granite statue of Ramessu II (fig. 43), of which an entire view is given in fig. 11. The whole pose is fairly good, the face looking down toward the spectator below. The king is no longer the dignified organiser of the Old Kingdom, with a vision far away beyond everyday matters, but he is obviously considering the opinion of the man in front of him. The detail is almost equal to that of the previous dynasty; the eye is natural, the nose rather formal, the lips with the sharp edge even more developed than before, and the chin and throat less modelled. The elbow is carefully wrought, bringing out the fold of flesh and the muscle separately, the accuracy of which is questionable.

A good example of a private sculpture is the head of Bak-en-khonsu (fig. 44). The eye is only slightly indicated, leaning to the conventional blocking out seen in figs. 91 and 137. The profile is good, and the lips are less exaggerated than in the royal statues. The artist could give all his attention to the face alone, as the figure is entirely hidden in an almost cubic block, which represents the man seated with knees drawn up before the chest.

The head of Merenptah (fig. 45) shows him as inheriting and imitating his father's face and attitude. The style is cold and formal; the eyes are so forward as to be even beyond the plane of the forehead, and scarcely capped by the brow. But the nose and lips are natural and free of the forcing which is seen rather earlier. There is no attempt at any delicacy of facial curves, and the chin and throat are masked by the official beard. As this is in gray granite, and was executed as the ka statue of the king's personal temple, it may be taken as the best that could be done at that time.

43. Ramessu II 45. Merenptah.

43. Ramessu II 45. Merenptah.

44. Bak-en-khonsu 46. Taharqa.

44. Bak-en-khonsu 46. Taharqa.A different feeling comes in with the massive individual portrait of Taharqa (fig. 46). The facial muscles are strongly marked, but the mouth is singularly unformed, and is exactly the opposite of that in the strong type of fig. 34. The eyes are of the gibbous form, with a long slot of lachrymal fossa, which is also shown in the kindred figure of Queen Amenardys (fig. 47). The style is not akin to any other Egyptian work, and it seems as if an entirely different physiognomy had challenged the sculptor and made him drop his usual treatment and study Nature afresh.

The alabaster statue of Amenardys (fig. 47) is disproportioned as a whole, though parts are good separately. It has just the faults due to an imitator who does not trust to observation. The head is too large, the jointing is weak. Each of the features is fairly well rendered; and within the limits of later mannerism there is no forcing or exaggeration.

The portrait of Mentu-em-hat (fig. 48) belongs to the same style as that of Taharqa, and both are in black granite. The eyes seem too small, but this is rather due to the depth and massiveness of the jaws, which overweight the face. The apparent disproportion in the low forehead is only due to the photograph being taken too close and low down. The height above the eyes is really equal to that down to the upper edge of the chin. The facial curves are carefully observed, and we can well credit this with being a true portrait of the capable governor of Thebes who continued in office under Taharqa and Tanut-amen, and who repaired the devastations of the Assyrian invasion.

A head broken from a statue, found at Memphis (fig. 49), is remarkable for the deep and searching modelling. The bony structure, the facial muscles, and the surface folds are all scrupulously observed. The artist's triumph is shown in the harmony and the living character which he has infused into his laborious precision. Very rarely can a man rise superior to such a rigorous training. The character of work is scarcely Egyptian; it belongs rather to the same school as the republican Roman portraits, but is earlier than those, as it has more precision of detail.

Late Sculpture

47. Amenardys 49. Basalt head.

47. Amenardys 49. Basalt head.

48. Mentu-em-hat 50. Wooden head.

48. Mentu-em-hat 50. Wooden head.Lastly, we have one of the best examples of Greek influence in Egypt shown by the wood-carving of a coffin (fig. 50). The long narrow face shaded by thick wavy hair is Greek in feeling, while the feather head-dress is old Egyptian. Unfortunately, the decay of the wood has broken the surface, but it still remains an impressive example of Egyptian influence on art which is mainly Greek.

Read more: http://chestofbooks.com/arts/ancient/Ancient-Egypt-Arts-And-Crafts/The-Statuary-Part-4.html#ixzz20c9Omyfy

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario